I learned to backpack in Colorado, California, Arizona, through desert, canyons, timberline passes and rocky ridgelines. Food was kept in the tent, campsites required nothing more than clear and flat ground, and often the travels were thought of in terms of distance covered or elevation gained. In general, even the more extreme outings were well controlled excursions with predictable itineraries and Indian Summers. For the Continental Divide Route, all of this has helped only in the most elemental ways.

|

| Henry on the summit of Summit Mt. Light flurries of snow coming down. |

In the second mile, I learned my National Geographic map was near useless. In the third mile, I realized both a new need for gloves (protection from rocks) and the seriousness of this route. I’d taken a forty foot tumble, sliding down scree, gaining momentum after going over a four foot cliff, digging in my heel and stopping just a foot shy of an eight foot cliff. When I stopped I had to sit there for a minute and make sure nothing was broken. The mountains had let us know early on that a fatal error is easy to make in this terrain. I also learned I have an allergic reaction to wasp stings. And, regretfully, I realized I can backpack even lighter, but that my largest weight cut must come from Nutella. I’ve never had to admit that a two pound jar of Nutella is too much to bring for a three day outing, which I think must qualify this route on a realm above all others I’ve done. The Continental Divide Route (CDR) is full of tough love.

It’s a beautiful, remote, dangerous, and staggeringly large undertaking. 110 miles, mostly off trail, traversing valleys where not only will you not see another person—there likely won’t be another person in the entire valley. Ski down scree chutes, wade through mountain streams, follow goat paths for hours, sleep next to bear scat—if Jim Bridger, mountain man, were still alive he undoubtedly would have done this route. The goal is to find the most elegant, non-technical line that stays close to the Continental Divide. Originally the goal was to stay within a mile, but glaciers/cliffs have caused me to reroute in order to find something more akin to my skill-set. Once I find a route, and feel I know it well enough, a single push effort over two or three days seems like a good undertaking to consider (so long as it doesn’t involve an undertaker).

My first scouting trip, with Henry Reich, ended when we descended to Upper Two Medicine Lake, hoping to return to the Divide at the saddle above the lake, which appeared to us as a sheer 200 foot cliff with rotten rock. After a brief excursion via trails to Dawson Pass and experiencing gale force winds, we decided to leave the next section of the divide for another excursion. Post-hike, we learned of a notch, hidden from our view, leading to the saddle from Upper Two Medicine Lake. I began planning, then, for a second trip.

|

| Leaving Buttercup Park at dawn, unnamed lake |

|

| Descending Mount Helen, towards human trail at Dawson Pass |

|

| Looking towards Split Mountain from Mt. Norris (the Divide goes left, following the white line in the shade) |

|

| Mt. Jackson in the background, Blackfoot Glacier in the foreground |

|

| Icefall below Blackfoot Glacier |

As I’m writing this, I’m studying the south ridge of Gunsight Mountain via Google Image search. No guide book or website mentions it as a viable route. The west side of the ridge looks horrendous, but the east side looks like a maze of diagonal, vegetated shelfs and likely hidden chimneys, all high above a large snowfield leading down to a waterfall hundreds of feet above Gunsight Lake. This is the part of the route, I’m guessing, that demands the most attention—there is no easy way, and no written information available to indicate the way. The upper section of the ridge looks like easy hiking on scree, all guarded by the cliffs below. From the picture I’m studying, it’s difficult to tell if a cliff is six feet or fifty feet, and all but the last wall of cliffs looks entirely doable, though there is one apparent line of weakness in the upper cliffs. If it goes, the rest of the route is at least vaguely described or on easy terrain. If it doesn’t, I may spend the rest of that day searching for a line.

|

| The eastern side of the south ridge of Gunsight Mountain in the early morning |

I received an email, in response to an inquiry about Gunsight, from the only man who’s traversed GNP within a mile of the Divide. His response:

You probably won’t like my reply. I respect what you are trying to do, but I’m going to tell ya that you’re going to have to go out there and connect the dots.

He went on to write,

If you get in a serious jam and need a tip, let me know. But the real challenge I suggest is that you go to GNP, and find the route. That is the true challenge…. the best adventure you’ll ever go on.

Take care and good luck,

Richard Smith

FOUR DAYS LATER

Well, I’m back and mostly just hungry and tired. My diet this past day has included more ice cream than usual, more napping, more doing nothing. Gunsight Mountain went more easily than expected, but it’s still not a place I’d want to be in adverse conditions. The ascent over Gunsight marked the end of remoteness in this last trip. I hadn’t seen anyone for a day and a half, and about the only word I’d spoken to myself was, “Wow!” several times.

Sometimes you don’t need a guidebook, maybe just Google Maps and some common sense. Nearing the top of Gunsight, I was at over 9,000’, above snowfields and the Sperry Glacier, and I’d just gone up a mountain without following anything other than intuition. This was maybe the most free I’d ever been. An hour later, approaching a family out on a side hike from the Sperry Chalets, my first encounter with the rest of the world would be to take their picture. What is scenery without a face in it?

|

| This guy didn’t ask me to take his picture |

|

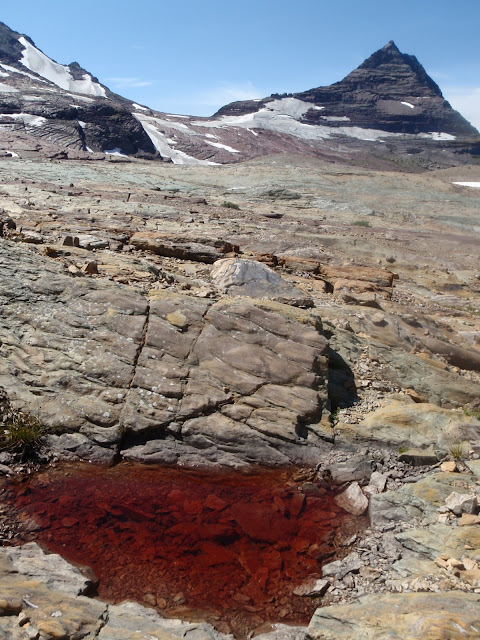

| Red pool, Sperry Glacier Basin |

As I approached Logan Pass, people started trickling by. First a few parties doing the Floral Park Traverse, then groups lounging on the Hidden Lake Shoreline, and beyond the pass it became difficult to continue apace, having to watch out for erratic movements of five year-olds, making sure not to photobomb anyone’s picture, and working harder to pass people who speed up when they realize they’re about to be passed. Mentally, this felt like one of the most difficult miles (hiking in convoluted crowds feels more taxing than hiking up convoluted cliffs at times).

From Logan Pass, I took trail out to Granite Park and camped there. This was my first night camping in a designated area, and the experience was odd. People talked a lot about gear. I didn’t have much in terms of fancy gear—just lightweight, simple stuff. Dinner was refried bean mix with water shaken up in a small peanut butter jar (I learned that from Henry). People asked me what all I had in my pack, since it seemed so small for such a large trip. I was beginning to realize that my pack was so small and light partially because I hadn’t brought much food. For snacks, all I had left were ginger snaps, three Kashi bars and dehydrated banana slices. Perhaps I should have packed that whole jar of Nutella this time.

Ten miles or so of hiking the next morning brought me to Fifty Mountain Camp. I was tired, lower on food than I’d like, and the next good spot for bailing was after twenty miles of cross country terrain. Smoke filling the Lake McDonald Valley didn’t bode well, either. Getting out at this point was still an adventure—Fifty Mountain may be the remotest one can be in the park and still be on a trail. Three hours of hiking to a boat dock, then a fifty minute boat ride across the lake, and five hitches took me back to my car nine hours later. The ranger at the boat dock had seemed very suspicious, and questioned what time I had started hiking the 23 miles from Granite Park to make it there at 1:30. Though Glacier may be one of the best parks for fast backpacking trips (or fastpacking, if you’re hip), the tight regulations make planning such a trip more difficult than doing it.

|

| Leaving Glacier’s high country as smoke fills the McDonald Lake Valley |

After arriving at the trailhead in time for the second boat shuttle of the day, I arrived in Waterton at 3:10, ten minutes later than the only southbound shuttle leaving from the Prince of Wales Hotel. Apparently, the boat shuttle company and the van shuttle company have never bothered to sync their schedules, probably figuring no one would ever use a combination of the two. So I hitched. The first ride was from a Canadian, and the only driver who went out of their way to take me farther south. I felt very unworldly looking at the speedometer and seeing kilometers displayed on the outside, and marveling at the slight differences in road signs. Perhaps out of duty to his country, he took me all the way to the border.

I’m not used to borders, so I was unsure what to do, crossing it on foot. Do I stand in line, behind the RV rental, and wait? That felt odd. Or do I cut ahead of the RV and the motorcyclists and just walk right up to the window? That felt rude. I must have seemed confused, because someone very official looking came out and checked my passport, inquired of my method of travel (hitchhiking) and told me to walk right on through.

Four rides later, I realized I’d gone a pretty long ways. The last ride was in an RV, with two retirees who seemed like Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau in the Odd Couple, except from Nashville. They offered me a beer, and were very energetic and cordial. This may have been because I was at a further distance from them than the other drivers, who could probably smell whatever the hell three and a half days in the mountains smells like.

It felt nice to be a passenger, and see the mountains fly by. So little of what I’d done was visible from the road, but piecing it all together from the map I could imagine the valleys on the other sides of the mountains, leading up to the Divide. The air was becoming thick with smoke, and the area around Gunsight Pass was totally obscured by a mass of grey. This was Glacier—the RVs, the fires, the gentle Canadians, the picture-aggressive day hikers and the rangers on the prowl protecting whatever it is that’s protected by the backcountry permit system. I had been there and was ready to return, again, to find what lay past Fifty Mountain Camp in the largest cross country section of the route.

FOUR DAY LATER, AGAIN

The race against the fires ended. I learned of the Waterton Lakes fire when I called the backcountry permit office, and have postponed the last section until further notice. It’s my weekend and I’m staying in town for once, which feels suddenly strange.

This route has already taught me more than any race ever has. I’ve learned to be a little less success-oriented, and more about just getting out there. Ever meticulous in my training log, this route is the one huge question mark. I’ve no idea how long I spent on my feet, or how much gain I did, or distance covered. Covering some of the most spectacular country I’ve been in, with so little written about, most of it utterly alone, has caused a shift. I feel good, I feel great, but I don’t feel focused. I just feel energized. Running right now, for me, is just about getting out and feeling the movement, with less a focus on numbers. It feels really good. I’m anxious to see what a few more days exploring Glacier’s backcountry can do, if the fires permit me to return and finish the route.

runwildmissoula.org >>

runwildmissoula.org >>